Emily Kame Kngwarreye: a deep-dive into the dreamtime & praising the yam queen in context

- Aug 11, 2022

- 13 min read

‘Kame [yam seed], that’s me.’

This was said as Kngwarreye cupped her hands together

in the manner of intekwe, the pod that holds the kame seeds.

- Christopher Hodges, artist and director of Utopia Art, Sydney

Emily Kame Kngwarreye emerged as the most celebrated artist of the Central Desert, and perhaps the whole of Australia, through a short but prolific career in painting.

To fully appreciate and comprehend the power of her art, we must be informed of the socio-cultural changes of the Aboriginal people imposed by the devastating colonial history that seethes beneath the surface of contemporary Australia.

Before We Begin; A Note

This blog post is based on a university essay I wrote ten years ago, aiming to place Emily within the realms of modernism whilst maintaining her roots in traditions. I was studying Oceanic Art under the esteemed Dr Peter Brunt. It was an extraordinary journey that changed my outlook on life and is largely responsible for my worldview. Exploring the art and culture of Pacific people, particularly the insights of the Aboriginal Australian peoples, have rearranged and reformulated the bedrock on which I approach almost everything. Their connection, not only with the world around us. but the world in which this world exists, has brought me great peace. To breathe life, above and below and in between all at once, brings me disembroiled comfort. I - in contradiction to the traditional Aboriginal experience - have had little understanding of home in relation to place. However, I do comprehend my life in a similar mapping and what has been characterised as the Dreamtime, the Everywhen, is the bloodstream and the colour of my own existence too. Although the story of it is, perhaps, diluted with my own retelling and interpretations, I hope you can see it is not within my intentions to cheapen sacred knowledge or misinform. I hold great reverence for the beliefs that have shaped and given confidence to my own. I am forever grateful it has been part of my path to study and love the work of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, and the culture and philosophy of life she has gifted to us through its creation.

Some Initial General Context

Initially deemed ‘primitive’, it is only fairly recently that the recognition of the sophistication and skill involved within Aboriginal art has been considered. Over a casual two-hundred years or so of oppression, it was largely disregarded or ethnographically misplaced; classified as curios and flung into museums, representing the primal beginning of man and allowing for gross stereotypes to set in.

Yet the startling electricity of Emily’s work confronts many Western viewers in its modernity and in her innovative departure from the generic concentric circle composition.

In the 1930s, the nation was in the process of searching for a developed art form that was completely Australian through and through. This would take the greatest aspects from the Australian School of Landscape Painters, European Modernism and Aboriginal art.

Australia failed to realize the timeless originality of their indigenous peoples until trendy art centres such as New York and Paris began to take interest in them.

French philosopher, Ricoeur understood traditional practices could not remain static but should acknowledge the past in order for invention to arise within the current climate of globalization; “civilizations confronting each other more and more with what is most living and creative in them” will reveal “human truth”.

When considered in this context, the acculturation that acrylic desert painting displays allows it to be described in terms of the global arena, as opposed to merely the locality of place.

Know your Roots, Know your Yams

The Anmatyerre language group is located in a remote area of the Simpson Desert known as Utopia. Emily’s paintings were, and are, contingent on her position as an Anmatyerre elder, combined with her experience of Dreaming over the course of her entire life, which came to a close in 1996.

Her birth country of Alhalkere had no contact with the white man until she was ten years old in the 1920’s. However, she did not pick up a paintbrush until a ripe age of around eighty.

Instantaneously, she received attention from critics, collectors and other artists. Her style has been compared to the Abstract Expressionists, perhaps in the palpitating resonance that flows through the paintings and the permeating mood that is suggested in her pigments. But with such sporadic visits from Europeans and oblivious to the existence of Pollock, this demands a goddamn logical Western explanation.

To understand Emily’s art, and any Aboriginal painting, is to understand the cultural context, their traditions and worldview.

Dreamtime: a Glimpse into the Otherworld via the Aboriginal Mindscape

From a typical, canonical European perspective or maybe just on a superficial level, the art of the desert appears abstract and schematic in the various shapes, dots and lines. Yet it is a complex and meaningful representation of the landscape that simultaneously expresses their intimate and unconditional relationship with it.

Big Yam, 1996, acrylic on canvas, collection of the National Gallery of Victoria

However, the full force of their artworks effects only initiated members of the clan that produced it. Adults, in particular those who have participated substantially in religious life, gain the deepest reading of Dreaming paintings.

For Emily, her Dreaming is the source of her creative drive and the knowledge she translates upon the canvas. Alhalkere is the inspiration for virtually all her work but the truth of her paintings stretches much further than this because of the elaborate explanation for Aboriginal topophilia, which is related to the Dreamtime. This photograph from 2007 captures a particularly striking shot of an arch formation of the Ancestor Rock at Alhalkere.

Elders such as Emily have access to the most secret spheres of sacred knowledge; which has been transferred across generations for thousands of years. How is that for esoteric? Much Aboriginal artwork remained undiscovered for an extended period of time due to this exclusivity and the ephemeral nature of its traditional forms. The first settlers of the nineteenth century regarded them as a society that created no art at all, when in fact they possess the oldest, perpetuating art practice known to humankind.

example of contemporary Aboriginal Rock Art; the famous Lightning Man’ at Nourlangie Rock, Kakadu, attributed to known artist, ’Barramundi Charlie’ Najombfolmi, during the 1963-1964 monsoon season

Traditionally, creating art is woven into the fabric of daily life; from telling stories to the children whilst tracing symbols into the sand, to body painting with natural ochre associated with spiritual activity. Thus, it provides harmony and order through the various stages of revelation, allowing the elders an element of control over the young.

From an early age, all are encouraged to draw, paint or weave and although only some of them will pursue these paths, they are all learned in the codified graphs of their clan, making their art a type of visual literacy. The largest amount of art is made for ceremonial occasions and generally most Aboriginal art reflects the Ancestral Realm, or Dreaming as it is now understood globally.

The term Dreaming is an inaccurate translation that suggests Aboriginal people float around in a fantasy world like infants but their religious systems and sense of spirituality are far from primitive.

The Dreamtime refers to the dawn of time and the shaping of the earth’s face by the Ancestors who hail from a subterranean spirit world. But Dreaming is not a time that has merely passed but coexists with reality. It is an existence and it simultaneously sustains life, bestowing energy to all plants, animals and humans.

Aboriginal spirituality is centred on this Lifeforce and through the commemorative rituals, the people are able to generate it and cultivate it. The rituals themselves last no more than two minutes but require six hours of preparation recreating designs and objects of ancestors to the sounds of sacred songs.

Governing life in the desert, Dreamtime presents the indigenous with a profound philosophy, and gives reason for their deep connection with the earth and their topophilic relationship with certain locations.

Traditionally hunter-gatherers, without buildings and other permanent structures, the location of certain events accumulates a sense of historical significance whether it be personal or clan related. Thinking in this mind-frame means a person’s life is mapped onto the landscape, which is correspondingly an objectification of themselves.

Emu Woman & Beyond; Reading Aboriginal Art, Traditional to Contemporary

Aboriginal art is religious in its purpose, motifs and practice. Emily’s contemporary forms can be considered within the European market and are hung in galleries. They are still traditionally derivative but approach the new mediums of acrylic paint and canvas with a fresh and creative manner. With most modern Aboriginal art, myths and access to the Dreamtime provide the artist with an insurmountable array of symbols and imagery seen in many of their paintings.

Emu Woman, 1988–89, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 92.0 cm x 61.0 cm (The Holmes à Court Collection, Heytesbury)

Emily’s first painting, Emu Woman, reflects much of her artistic practices and was the work that thrust her into the limelight of international fame. After a lifetime of creating traditional Aboriginal art, her cultural narratives found a new mode of expression in the fluidity of wax in batik which was introduced by Jenny Green to the women of Utopia, easing the transition to painting.

The Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA) delivered to Utopia one hundred blank canvases in 1988 as part of a community-wide painting project and thus Emu Woman was discovered. It proved to be a captivating combination of tradition and innovation in the new medium. Challenged with the confines of working within a rectangle, Emily adapted to the surface and began with linear patterns that evoke ritual designs and the formations made by root systems of plants.

Many Aboriginal paintings serve as mnemonic maps, arranged as if from a bird’s eye view looking down from the heavens and, almost topographically, into the land itself. The Dutch artists of the seventeenth century also found an affinity between maps and painting. Both demonstrate a revelation of knowledge and pose the metaphor for one’s life journey.

However, Emu Woman mainly depicts graph designs that emulate the lines and contours of body painting for women’s ceremonies, praising the Emu ancestor. Aware of the public gaze, she protects the sacred information by pushing abstraction and instead presents the Ancestral Realm through rhythmic, gestural movements in a thick impasto. She also communicates through an aesthetic arrangement of dots over the surface, perhaps visualizing seeds or the sand on which she would have created ceremonial ground paintings countless times. Emu Woman illustrated to a global audience that Aborigines are more than capable of creating a dialogue with the West.

Papunya Tula Changing the Game

As Aboriginal communities have faced the dispossession of their land, and the deprivation of their cultural identity due to colonisation and the rigid limitations of eurocentricity, they also faced changes in aesthetics. The Northern Territory Land Rights Act of 1976 brought forth the outstation movement that saw Aboriginal people return to their lands.

However, repercussions of prior injustice, which included inadvertent genocide of the Stolen Generation; children who were assimilated into Western society, are deeds that are difficult to undo. Yet, there are several efforts made to reconcile the past.

Geoffrey Bardon’s post as an art teacher at Papunya School in 1971 sparked one of the most prominent art movements of Oceania by simply offering paint to the Aboriginal groundsmen and cleaners. The practice of art has breathed vitality back into their culture, attracting the young and creating legitimate income in the foreign regime of the whitefellas.

It has freed them from banal tasks that government officers prescribe in desperate attempts to reduce unemployment, when in actuality there are no genuine jobs for them within European ideas of progress and the quest for economic expansion. Emily has brought pride to the people of Utopia through her art which has managed to build a bridge between cultures in its communication of Aboriginal plights and beliefs.

Emily KK's Artistic Developments

Emily’s painting style continued to flourish, expanding with the sheer size of the canvases that grew ever larger, suitable for the subject of Dreaming. The evolution of her style can be followed in the excessive use of dots seen in Yam. They are scattered across the plane like seeds or constellations of stars, shrouding the under-tracking pathways that refer to Ancestral journeys and disguising the relations between places and people.

Yam, 1989, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 90 x 60 cm, the Holmes à Court Collection, Heytesbury

Playing a functional role within the art, Emily exceeds the Impressionists in her employment of the dot. They appear to be applied in various sizes and in certain rhythms that allude to ceremonial dancing whilst her command of colour conveys the shift in seasons and night skies of the desert. Her painting signifies an Aboriginal discourse in the consideration of her culture and country, conjuring its magnificence to a deaf civilization that marginalized her from its benefits.

interesting lil snippet discussing Emily's process through one of her works

As Emily continued to hide sacred knowledge from the view of the public, she methodically enhanced her technique with an unrivalled eloquence, surpassing her fellow Australians.

Her ‘high-colourist’ phase shows a dashist romance with dots, reminiscent of early Kandinsky paintings. It is also often compared to Monet's Water Lilies. The huge scale captures the vast desert, the stretch of her life and the Dreaming. Earth’s Creation displays a fusing of dots which create dappled areas of colour that swirl and propel dynamically across the canvas.

Similarly to Yam, the work embraces ceremonial dances and her palette is determined by the seasons. Lush greens of fresh foliage spread after the rains, making the earth gush with new life. This celebration of her country, springing into birth may reflect her success in the art world; which is appropriate as Earth’s Creation became the first Aboriginal artwork and the first painting by a female Australian artist to hit a million dollars in 2007.

Earth's Creation, 1994, acrylic on canvas, 275.0 cm × 632.0 cm (108.3 in × 248.8 in) National Museum of Australia, Canberra

This illuminates the issue of the selling Western Desert art as a commodity or any other pretty picture. Most Aboriginal artists feel dubious that white people will ever understand their paintings or way of life as “they know that white people don’t understand and don’t make the effort to understand.”

Nevertheless in the case of Emily, her works have a gravity of their own, pulling people in from across the oceans, instigating hope for ecumenical understanding. Questions are raised about the authenticity of modern Aboriginal art; the syncretisms of such paintings bare techniques that already existed within the culture but are now refined and developed.

Emily’s work is traditional in all aspects but rather exhibits Aboriginal reality as it exists today. The indigenous are aware of their position in Australian society and a European reading into their works may conclude their art as a political statement, legitimizing their world view through asserting their claim to the land.

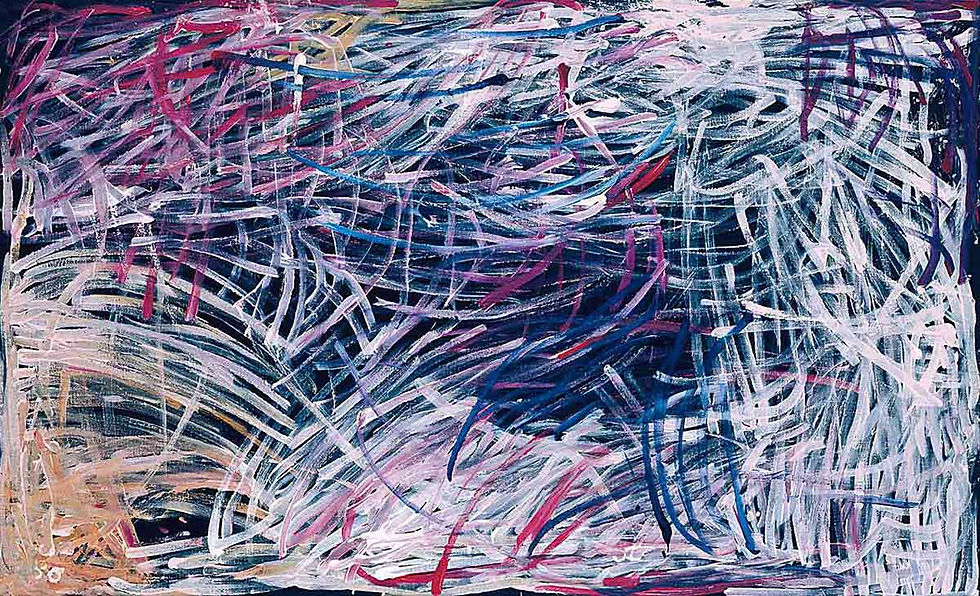

Eventually, Emily abandoned dots for bold, minimal linear patterns that comply with her earlier works in the evocation of ceremonial body painting.

Untitled (Awelye) appears as a schematic abstraction of her previous technique of under-tracking. On an international scale, these thick, recurring stripes can be placed alongside Western concepts of modernism.

In the largest, overseas, solo exhibition of any Australian artist, Emily Kame Kngwarreye was truly elevated as one of the great modernists of our time.

This is Visual Literacy

Japanese audiences observed parallels with calligraphy in the powerful rhythm of her brushstrokes. Both these art forms are modes of visual literacy; Aboriginal symbols cannot be equated to a rule-bound alphabet as each possesses several meanings that depend on their context.

European contact instigated the impetus to decipher their meanings, but with the emergence of Emily’s work, therein signals a break from iconic modes of Aboriginal art and also a break from the conventional narratives that accompany them. Dreaming stories direct the viewer to a strictly narrative interpretation whereas Emily invokes the multiple layers of earthly and cosmological imagery in order to inspire the sublime in the viewer.

She seems to focus on the process of painting, of channelling the Dreaming as opposed to describing it with imagery. We can read her work as a type of shorthand, in their swift completions, capturing only the essential information.

The line is most potent in Emily’s Utopia Panels. The series, painted in the last year of her life, are truly the artist’s magnum opus in their modernist rendering and the transition into an art that swings towards conceptual. Acknowledging the history of her people, the size and shape are reminiscent of the Yuendumu Doors which in turn nod towards the murals at Papunya. Traditional paintings were completed on the doors of schools in order to remind children of their heritage in fear that “they might become like white people which [they] don’t want to happen”.

The effects of colonisation are most prominent in the introduction of writing; from Christian missionaries preaching the word of the Bible, to the supposed need for documentation and schooling – the beginnings of integration into white culture.

However, the seven panels swallow the viewer in repetitive waves of black and white, devoid of her usual luminous colour and thus subverting expectations of Aboriginal art. The imagery is disquieting in its violent relentlessness, our eyes reading across like the pages of a book but also down and through the panels. Echoing modern day Australia and mass production, the panels certainly evoke typefaces and their oppressive effect.

Have a scroll through this:

The graffiti artist and art theorist, Rammellzee wrote the Ionic Treatise Gothic Futurism, describing the symbolic battle against standardizations of letters, enforced by the rules of the alphabet. His letters were “armed to stop all phony formations, lies, tricknowledgies placed upon its structure”. Emily’s approach is less militant but similarly, she fights the orthographication of the Aboriginal language.

Yet, without standardizing the language into an alphabetic form, such progressions as the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 could not have been carried out. However, the ultimate downside to this is the possible assimilation of Aborigines into a European mindset. It's one of those things.

Emily explodes into modernism, not through painting but through her exposure to writing. In a rebellion against these forces, she brings forth the milieu of her life within the context of land rights and their harrowing effects that continue to this day.

Unlike Rammellzee, there are no letters to be seen in the Utopia Panels. And here, she presents her highest mockery. There is no code to crack or writing to translate. Collectively, the panels create a seamless illusion, forming a large screen of static and consequently, nothingness. Her furious, rapid lines are totally illegible across the panels, harking graffiti, which is abundant within Aboriginal society.

Graffiti offers an expressive form of writing that cannot be practiced within school and the workplace, and grants the opportunity for a new found identity amongst Aborigines. Both graffiti and Emily’s work transcend oppressive limitations and are ubiquitous. Emily’s lines trail off the canvas as if continuing out into space, always evoking the Ancestral Realm. The lines themselves show evidence of calligraphic brushwork, stopping and starting in measured but organic rhythms. The surface swells and pulsates with the energy of the Lifeforce.

The modernism of Emily’s expansive style can be explained through her traditional source of creativity. The Dreamtime; its omnipresence and eternal nature provides endless inspiration that is also fluid and therefore is able to correspond with colonial and post-colonial activity. Thus traditional values are open to change and by slipping into abstraction effortlessly, Emily proves the universality of Aboriginal cosmologies and aesthetics.

By revolving around the Dreamtime, the process of her painting is therefore always ‘authentic’ and conforms to post-modernity through the continuum of the past, present and future. Emily’s work is, in this sense, strictly Australian Modernism, shaped by her changing environment and can speak with authority about the nation state to an international audience.

Notes & Recommendations

Papunya: A Place Made After the Story by Geoff Bardon and James Bardon

Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art: Collection Highlights, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra by Franchesca Cubillo and Wally Caruana

Transformations in Australian Art, Volume Two: The Twentieth Century – Modernism and Aboriginality by Terry Smith

Ancestral Modern: Australian Aboriginal Art by Pamela McClusky, Wally Caruana, Liza Graziose Corrin and Stephen Gilchrist (eds)

Aboriginal Australian Art: A Visual Perspective by Ronald M. Berndt & Catherine H. Berndt with John E. Stanton (eds)

'Art of the Desert’ in Aboriginal Australia by Nicolas Peterson

'Utopia' by Christopher Hodges, featured in Aboriginal Art and Spirituality by Rosemary Crumlin (ed)

‘Emily Kame Kngwarreye’ by Deborah Edwards, featured in Tradition Today: Indigenous Art in Australia by Watson, Ken Watson, Jonathan Jones, Hetti Kemerre Perkins (eds)

Breasts, Bodies, Canvas: Central Desert Art as Experience by Jennifer Loureide Biddle

‘Global Indigeneity and Australian Desert Painting: Eric Michaels, Marshall McLuhan, Paul Ricouer and the End of Incommensurability’ by Ian McClean in Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, vol.3, no.2, 2002.

‘Materializing Culture and the New Internationalism’ by Fred Myers, featured in Painting Culture: The Making of an Aboriginal High Art

Comments